What will higher education look like in 2030?

The NMC Horizon Report 2017 defines two ‘wicked problems’ for the future of higher education, which are “complex to even define, much less address”. These are:

- Managing Knowledge Obsolescence

- Rethinking the Roles of Educators

Knowledge is important to enable people to understand and reflect on connections between objects, between physical and between social phenomena; to gain insights into them for understanding and perhaps in order to change them. The economist might want to change them for greater economic impact, the engineer for more efficient and new technical processes, the medical doctor or nurse for greater health and the social scientist to improve societal processes of participation and fairness. The educator’s task is to facilitate these processes through supporting knowledge and skills acquisition – didactics is about activating such acquisition. This challenge is not really changing at all, but it is becoming more important that more people in society become active and continual learners, constantly reflecting on what they know and can do, but also on the value and the sustainability of what they know and can do.

Dissolving boundary between being ‚in‘ and ‚out‘ of higher education?

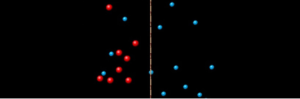

Even with the advent of distance and online modes of learning, higher education is broadly shaped by two limitations: (1) the difference between being ‘in’ and being ‘out’ of a higher education institution, i.e. mainstream higher education erects high administrative hurdles to entering a full learning programme (e.g. enrolling for a full programme of study, calling for standard entry qualifications, and only recognising learning ‘in’ higher education, not non-formal or informal learning); (2) the linearity of learning, i.e. the general idea that the foundational blocks of learning post-secondary education continue sequentially until a full programme of a Bachelor and perhaps even a Master course is completed, after that learning can be additive in smaller blocks, but generally does not increase the value of a person’s formal educational profile. This makes higher education exclusive to certain population groups (there are no higher education systems in the world, which fully reflect population diversity of the country they are based in) and leads to the increasing criticism that what is being learnt is outdated as soon as the graduate leaves the ‘institution’ higher education.

Flexibility of provision of learning which is not based on a common path of linearity (like climbing a ladder), but spiral shaped (interchanging spheres of depth) and which is not based on fixed content (‘knowledge canons’) is a challenge for higher education. However, openness of provision, unbundling of higher education programmes and closer, more individualised support of learners by educators are all being facilitated through digital solutions.

The future is already visible

It will be a major challenge for the AHEAD study to make predictions on what forms of higher education provision are most likely in 2030. But in our research we are already able to look to existing innovative practices across the world and to statistical and qualitative trends in skills and knowledge demand, learning theory and digital learning innovations, which will shape these processes on route to the year 2030.

This may seem a long time in the future, but the 8-year olds of today will be in tertiary education in 2030 (many of them undertaking some form of Bachelor course?) and the 18-year olds will possibly be their instructors. But also the 30 year-old across the road could be a Bachelor student in 2030. We are, then, surrounded by our future, which just have to recognise it.

Picture of process of osmosis from https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osmose#/media/File:Osmose3.jpg